The first half of the 20th century saw the birth of the aeroplane and its development as an instrument of war and commerce. A new book offers more than 170 carefully colourised period images of aircraft produced in Great Britain before 1950. Here Key.Aero presents an extract from British Aviation The First Half-Century

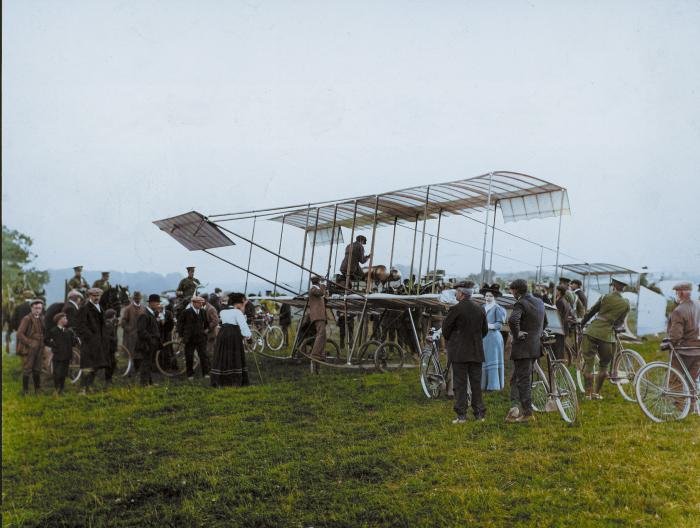

The first 50 years of the 20th century witnessed great leaps forward in many fields of scientific endeavour. For aviation, it included the first flight of a heavier‐than‐air aeroplane and the establishment of a new industry dedicated to designing and building them. The first piloted, powered, heavy‐than‐air aircraft to officially fly in the British Isles was the British Army Aeroplane No 1, designed and flown by Samuel Franklin Cody.

Cody was born in Davenport, Iowa. After moving to England, he tested a biplane glider in 1905 and was employed as the Royal Engineers’ kiting instructor within the Army Balloon Factory at Farnborough, Hampshire. The No 1 made its milestone flight of 1,390ft (424m) on 16 October 1908 but although testing continued into 1909 – flying for more than a mile (1.6km) on 14 May – interest within the War Office quickly waned.

Birth of an industry

Towards the end of the first decade of the 20th century, Britain’s aircraft ‘industry’ comprised of individuals working (usually) at their own expense to build contraptions they hoped would lift them off the ground. Those that were successful found that other people wished to have aircraft built for them. During the first ten years of the century, Robert Blackburn, John William Dunne, the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, Geoffrey de Havilland, Claude Grahame‐White, Frederick Handley Page, Noel Pemberton Billing, Alliott Verdon Roe, the Short brothers, Thomas Sopwith and Vickers were among those designing and building aeroplanes. Many of them went on to create firms that were to play an important role within the British aviation industry.

The period saw the adoption of the aeroplane as an instrument of war and the pace of development increased during the Great War as money and manpower was allocated to develop and design machines for the Admiralty and Army. The frail machines that set off for France in August 1914 were very different to the heavy bombers entering service with the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF) at the end of World War One in terms of performance, reliability and armament. More than 50,000 aeroplanes were built in Britain alone in just over 50 months, with general purpose designs giving way to those dedicated to a specific role.

The roaring twenties

Development of military aviation almost came to a halt after the war, due to the need to reduce government expenditure and the belief that there would not be a major conflict for at least ten years. Although the RAF was allowed to remain a separate military service – much to the alarm of the Admiralty and Army – it largely had to ‘make do’ with the aircraft designed and delivered to it in the latter years of the war. In addition to most outstanding contracts being cancelled by the government, the market for new, purpose‐built civil designs in the immediate post‐war period was effectively suppressed by the ready availability of large numbers of surplus military aircraft.

The 1920s are often described as aviation’s ‘adventuring years’. Flying combined an exotic mix of technology, escapism, adventure and glamour – and a fair degree of danger – that appealed to a generation that had witnessed the horrors of mechanised warfare in Europe and those that came of age soon after. Although still largely for the affluent, the popularity of flying clubs increased throughout the decade, providing access to the air for many of lesser means.

The decade also saw the RAF forge its own identity as a separate service with a distinctive role under the leadership of Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff from 1919 to 1929. It offered a cheaper method of policing the colonies than garrisoning large numbers of troops overseas or calling upon the stretched resources of the Royal Navy. As the decade progressed, the importance of the RAF also grew in the British Isles as the theories of the proponents of air power began to circulate. These include the dogma that ‘the bomber will always get through’, first outlined by the Italian General Giulio Douhet, that strategic bombing would force populations to sue for peace within months and the only defence was offence. Trenchard also believed that the bomber would be the key weapon in any future conflict and, in 1925, formed Air Defence of Great Britain to provide protection for the capital against the threat. By the late 1920s, more than 500 aircraft a year were delivered to the RAF, although the service only grew by about 50 annually as older types were replaced and attrition made good.

From peace to war

In the early years of the 1930s, British aviation recorded some notable achievements. In September 1931, Flight Lieutenant John Nelson Boothman won the Schneider Trophy seaplane race in a Supermarine S.6B, the third consecutive time the British team had prevailed, allowing the prize to be claimed outright for the country. On 3 April 1933, the Houston Mount Everest Flying Expedition, funded by Lucy, Lady Houston, became the first to fly over the highest place on the surface of the earth. Sir Douglas Douglas‐Hamilton (Lord Clydesdale) and Flight Lieutenant David Fowler McIntyre in the Westland PV.6 ‘Houston‐Wallace’ and PV.3 flew in formation over the ‘roof of the world’ for a second time on 19 April. Between 20 and 23 October 1934, Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott and Captain Tom Campbell Black won the MacRobertson Trophy Air Race between Britain and Australia in de Havilland DH.88 Comet Grosvenor House.

While these achievements – faster, higher, further – helped boast the image of the country as a leader in the air, by the middle of the 1930s, significant questions were being asked about the state of the RAF. The rise of Italian Fascism and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, both with ambitious plans for their air forces, caused alarm within official circles. In 1934, it was decided that the size of the RAF would no longer be pegged to that of France but Germany, and plans were formulated to increase it and expand the capacity of the British aviation industry. The expansion programmes were initially hampered by a lack of funds, but, as neighbouring countries began to be incorporated into the German Reich and the prospect of war loomed ever closer, additional sums were released by the Treasury for military spending. The outcome of this largesse was the introduction into RAF service of successive generations of fighters and bombers in the second half of the 1930s. Many designs quickly became obsolete as the state of the art for military aircraft advanced and, as the decade drew to a close, biplanes gave way to modern monoplanes, fighter armament increased from two to eight machine guns and performance improved as more powerful engines were installed and aerodynamics refined. The better quality was matched by moves to increase quantity and by the time war was declared on 3 September 1939, the foundations for the enormous wartime production programme were in place.

Total war

It was during World War Two – in 1944, to be exact – that the British aviation industry reached the peak of its output. With the nation configured for ‘total war’, production of aircraft had high priority, supported by and centrally planned by the Ministry of Aircraft Production to feed an almost insatiable appetite for combat aircraft for operations across the globe. In the early years of the war, the aim was to build as many combat aircraft as possible, with changes only introduced that gave a clear improvement in performance without disrupting the flow of aircraft from the factories. Several types that went on to play important roles in the later years of the conflict flew in 1940 or before, but development proceeded slowly because of the need to concentrate resources on existing programmes. This new generation began to enter service from around 1942 and while not all were successful – it is fair to suggest the outcome of the war would not have been altered if the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle had been cancelled – in general, the RAF was well served by the aircraft produced by the British aviation industry during World War Two.

It is more difficult to say the same about the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), which was somewhat neglected and equipped with less than first‐class aircraft during the 1930s, while the new generation of purposely designed British carrier borne aircraft that entered service in the second half of the war were adequate, rather than exemplary. To a large extent, this shortfall in performance was alleviated by large numbers of American naval aircraft supplied under Lend‐Lease.

This article is from British Aviation The First Half-Century Book

The first half of the 20th century saw the birth of the aeroplane and its development as an instrument of war and commerce. British Aviation The First Half-Century has over 170 period images, carefully colourised, this book chronicles the wide variety of aircraft produced in Great Britain before 1950, portraying them in their full glory once more.

Slow run down

At the end of the war, Britain was in a perilous financial position. Although it had prevailed, the conflict highlighted the military and industrial dominance of the United States and the Soviet Union, compared to which Britain was a second‐rate power. Balanced against the need to cut costs by reducing the size of the wartime armed services was the requirement to keep sufficient forces in occupied Germany, Italy and Austria and many other areas of the globe to maintain (or in many cases, restore) stability. In the Far East, many uprisings occurred in the former European colonies after Japanese forces surrendered, led by people eager to determine their own destinies before the British, Dutch or French ‘colonial masters’ returned. These global commitments helped slow the run‐down of the RAF, while suspicion over the intentions of the Soviet Union meant there was no post‐war equivalent of the ‘ten year rule’.

In 1946–47, the RAF accounted for 15.5 per cent (at £255.5m) of defence expenditure, just below that of the Royal Navy (16.1 per cent) and a long way behind the Army (43.4 per cent); a quarter of the budget was allocated to central defence needs and other governmental ministries. Unlike after World War One, procurement of aircraft for the RAF and FAA continued, but at a much lower level.

It was clear that the new generation of combat aircraft would be powered by jet engines, making the large existing fleet of piston engine types obsolete, and the post‐war era saw their development and introduction to service in increasing numbers. Britain had a lead in jet engine technology at the end of the war, but this was not matched by an exploitation of the aerodynamics that would have greatly improved performance. Plans for an aircraft to break the ‘sound barrier’ – the Miles M.52 – were cancelled in February 1946 and adoption of swept wing fighters was delayed until long after the US North America F‐86 Sabre and Soviet Mikoyan‐Gurevich MiG‐15 had entered service.

By 1950, the best the RAF’s Fighter Command had was the straight wing de Havilland Vampire and Gloster Meteor, both of which first flew during the war. At the same point, Bomber Command still relied on the Avro Lincoln – little more than a bigger Lancaster – and was receiving Boeing B‐29 Superfortresses (as Washingtons) from America; it was only in May 1951 that it accepted its first jet bomber, the English Electric Canberra, into service.

The impetus to improve both the quantity and quality of the armed forces came when North Korean invaded its southern neighbour on 25 June 1950, beginning a brutal three‐year war which saw China and the Soviet Union on one side and the United States and other members of the United Nations (including Britain) on the other. The early 1950s saw a build‐up of British military forces from which the aviation industry benefited.

Aircraft for the airlines

During World War Two, Lend‐Lease also alleviated the lack of modern transport aircraft produced by British manufacturers, with the Douglas Dakota (US Army Air Force Skytrain or Skytrooper) becoming the standard RAF freight hauler by the conclusion of the conflict. As the end of the European war approached, plans were laid for the design of several classes of airliners by both the government and manufacturers, with the aim of capturing a large share of the market post‐war. The immediate need for commercial airliners resulted in stopgap conversions of the Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax bombers as the Lancastrian and Halton, plus modifications of Short Sunderland flying boats as Sandringhams.

In addition, existing production types (such as the Avro York) and others adopted from originally military designs (including the Bristol 170 and Vickers Viking) became the first generation of ‘interim’ post‐war British airliners, while development of definitive types was undertaken. Unfortunately, while the demand for airliners across the globe was large, so was the number of suitable surplus military transports that could be configured for fare‐paying passengers. Coupled to the slow and often troubled development of many of the post‐war British airliners, this all but guaranteed that relatively few of the early designs would be built.

By the end of the 1940s, the great hope was the jet‐powered de Havilland Comet, which not only offered a significant increase in performance in terms of speed, but also better passenger comfort thanks to its pressurised cabin. At the start of 1950, it appeared that the Comet would be a ‘world beater’, a standard bearer for the British aviation industry in the second half of the 20th century. Tragically, it was not to be.

Golden age

The first 50 years of the 20th century was a golden age for British aviation. It encompassed the pioneering years, the great leaps forward sparked by the two world wars, the development of the airliner and the rise of private aviation. More different types of aircraft were built and flew in the British Isles during the first 50 years than in the 70 years since, while the total number of aircraft rolled out was far greater, reaching its zenith during World War Two.

Identifying the aircraft to adequately represent the period is no easy task. Although it is tempting to focus on the famous – the Sopwith Camel, de Havilland DH.60 Moth, Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire, Avro Lancaster – for each that became a household name, numerous others never even made it into the public consciousness. They include many types that flew only as prototypes, failed to find a place in the market, or served in pedestrian roles that never generated headlines in the newspapers. The story of the first 50 years of British aviation cannot be told without them.

If you enjoyed this article, you'll love the VIP Book Club

Membership to Key Publishing’s VIP Book Club is completely free. You will get access to big discounts and be the first to know when new books are coming out.

This article is from British Aviation The First Half-Century Book

The first half of the 20th century saw the birth of the aeroplane and its development as an instrument of war and commerce. British Aviation The First Half-Century has over 170 period images, carefully colourised, this book chronicles the wide variety of aircraft produced in Great Britain before 1950, portraying them in their full glory once more.